Blind Justice: The Life and Career of David Tatel

(Inspired by Vision: A Memoir of Blindness and Justice)

Strict Scrutiny Podcast today interviewed the author of this book.

I enjoyed the book and decided to write a short biographical piece.

The symbol of Lady Justice is blindfolded, holding the scales of justice and a sword to enforce the law. She is blindfolded to interpret the law without bias to either side.

We often subconsciously favor people based on appearance. Judge David S. Tatel has a step up on his colleagues. He is legally blind and not just metaphorically.

Just ask his guide dog, Vixen.

Early Life

David Stephen Tatel was born to Jewish parents (Howard and Molly) on March 16, 1942.

His family, including a younger sister (Judy), lived in Silver Spring, Maryland. His mom’s parents arrived in America on the last westbound voyage of the doomed Lusitania, which was a victim of a German submarine attack during World War I. His father was a scientist.

David found out at age fifteen that he had retinitis pigmentosa, a fancy term for an eye disease that would lead to blindness in his thirties. He did not know how bad his sight would become and tried not to let his disability control his life. David even registered for a driver’s license.

That was a bad idea. His vision, especially at night, was iffy even as a teenager.

Early Legal Career

Everyone thought Howie Tatel’s boy would follow in his father’s footsteps.

Nonetheless, David fell in love with politics and the law in college. Great changes were occurring, including the Supreme Court declaring school segregation unconstitutional.

He also was inspired by President Kennedy’s call for public service, working at the Labor Department during the summer. David went to law school and worked to promote civil rights. President Carter ultimately chose him to lead the Office for Civil Rights.

Becoming Blind

While in law school, David married Edie, who later became a teacher. They had three daughters and a son. David and Edie did not know at first how bad his eyesight would become.

Our society honored a few special disabled individuals, including Helen Keller (blind and deaf). Roger O’Kelley was the first deaf-blind lawyer in the United States in 1912.

The government passed certain laws to serve their needs. For instance, schools that received federal funding could not discriminate based on disability.

Nonetheless, there is much ignorance and prejudice. David tried to hide how bad his eyesight was becoming. For instance, he did not want to use a cane, fearing that he would be labeled as a “blind person.”

His body also compensated in different ways. An excellent memory and ability to visualize things helped a lot. Others helped by reading aloud and guiding him around.

We might want to deny reality but it has a way of showing up all the same. He finally did use a cane. The Library of Congress provided “Talking Books” for the blind. Over time, new and improved technology helped. Now, he can download an app on his phone that reads text.

Becoming A Judge

Our federal court system has three levels. District courts are where trials occur. There are thirteen courts of appeals, which review the decisions of district courts. One court of appeal only handles cases from the District of Columbia, the nation’s capital. The Supreme Court stands at the apex of the court system, hearing federal cases from state and federal courts.

President Clinton chose Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg to fill a vacancy on the Supreme Court. She was a judge on the D.C. Court of Appeals, the source of many Supreme Court justices, including Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson. Clinton chose David Tatel to fill her seat.

Judge David Tatel became the first blind federal Court of Appeals judge on October 7, 1994. Clinton would later appoint Richard Casey, the first blind federal trial judge.

Judge Tatel served for thirty years, retiring in 2024.

Blind Justice

Judge Tatel quickly became a greatly respected judge, including among conservatives on the D.C. Court of Appeals who disagreed with him on many issues. He believed in judicial restraint and rarely dissented. Many judges are principled, hard-working jurists. Few are legally blind.

He had many tools to help. Judges have to read a great amount. Each case involves multiple legal briefs. A judge has to write an opinion, which often goes through multiple drafts.

Tatel was helped by readers, often former debaters, who read everything, down to the periods and commas. On the bench, Tatel used a small Braille computer, listening through one earpiece as he clicked through his meticulous notes. Text-to-speech technology was quite useful.

It helps that he has an excellent memory. A reader or clerk had better not miss a comma!

Vixen

Judge Tatel did not want to use a guide dog. He thought it would take too much training. Tatel was not a big fan of dogs. And, wouldn’t a dog be a wild card? His life was good without one.

When David was seventy-seven, his grandson suggested he consider getting a dog. Guide dogs were used to help those blinded during World War I. They are carefully trained and matched up with their humans. Tatel took a chance. He soon fell in love with his dog, Vixen.

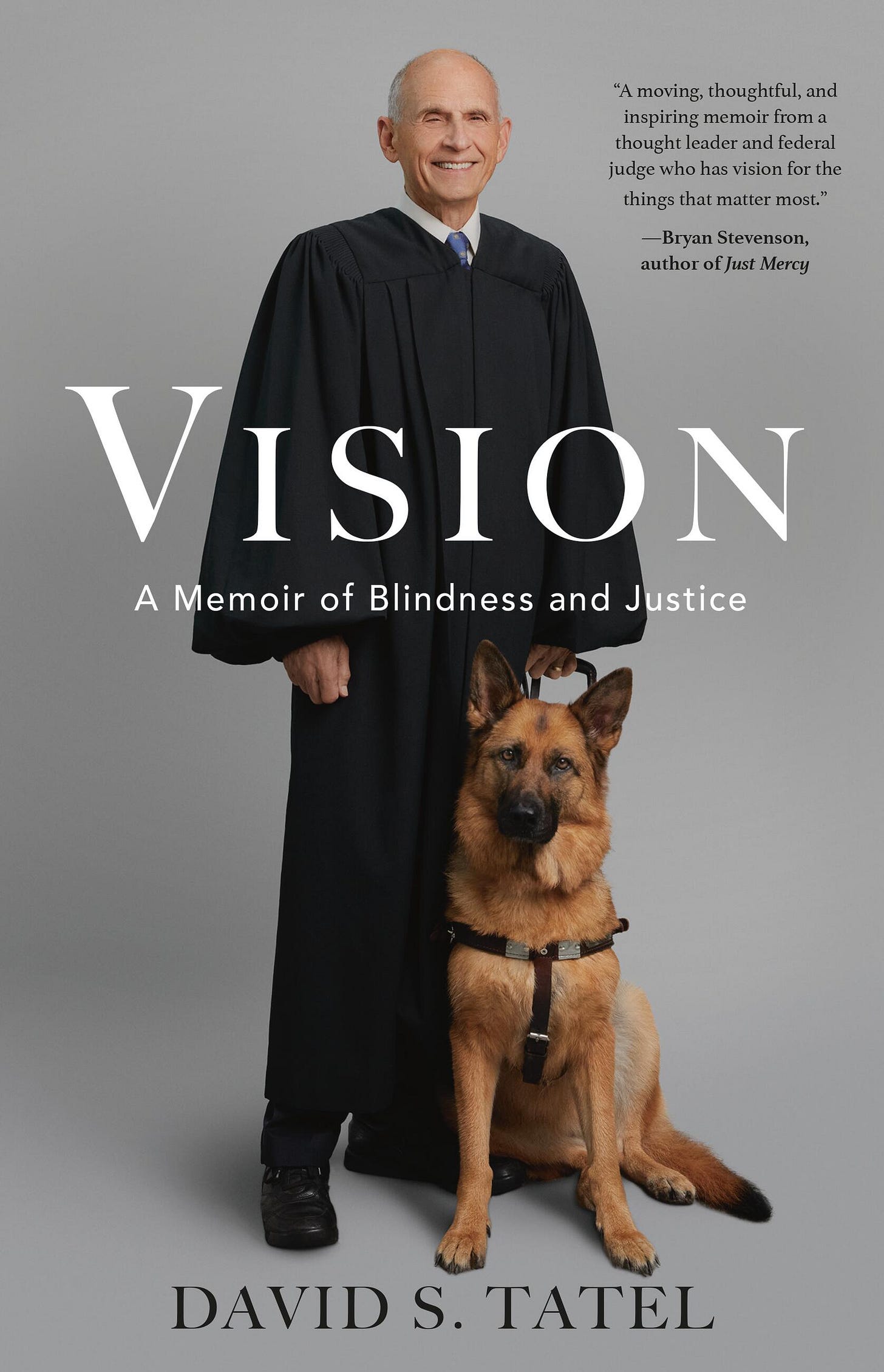

There are two photos in David Tatel’s autobiography (Vision). Both show him with Vixen, a beautiful and well-trained German Shepherd.

Both Judge Tatel and Vixen continue to enjoy his retirement. Meanwhile, judges with various types of vision continue to try to interpret the law following the ideal of Lady Justice.