Kristen Rogheh Ghodsee is an expert on Eastern European communism. She received some fame for Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism.

Her latest book is Everyday Utopia, concerning utopian movements throughout history. The book is somewhat longer than her others and I had trouble getting into it. Maybe, I will try again later. I will provide a book summary of an earlier book here.

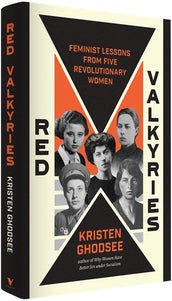

Red Valkyries: Feminist Lessons from Five Revolutionary Women by Kristen Ghodsee (Hardcover; 206 pages)

Brief Overview

The Communist Manifesto was written by Karl Marx and Frederich Engels in 1848. It spoke of a class struggle taking place with a chance of a workers’ revolution.

This dream of a united effort to reform society was part of a wider socialist and communist movement that inspired millions in Europe, the United States, and in time as far away as China and Indochina. A moderate form of socialism inspired our current social welfare state.

Women played a major part in this socialist revolution. Red Valkyries (“red” being the color of the communist revolution, “valkyries” being Norse heroes) talks about five such women, three who played an important role in the founding of Soviet Russia, one who was the top woman sniper during WWII, and one who played a leading role after WWII in Communist Bulgaria.

The book not only provides a look at the exciting lives and times of these five women but also shows they are role models. Not only do their ideas provide insights relevant to creating good social policy today, but nine specific qualities are singled out in a final chapter to serve as models for any successful effort. We should find inspiration wherever we can.

This is an inspiring account about women that few in the United States know much about, including the wife of the first leader of Soviet Russia. It is a great addition to the many other books by the writer, who studies and teaches about Eastern European cultures.

Favorite Quote

I have adopted the word [Valkyrie] for my title because each of the women profiled in these pages, in their own way, fought like superhuman warriors to support causes that defined the twentieth century. Their personal stories reveal certain similar characteristics that they shared, characteristics that made them successful in their quests to create, further, and defend social change.

Red Valkyries tells the stories of five women, four Russians, and one Bulgarian, who fought to promote socialist and communist ideals. Such women deserve to be better known and provide many lessons for our society, including to help guide us to form a better society.

Should I Read It?

Kristen Ghodsee writes about a subject that many people in this country know little about. After all, her specialty is Bulgaria of all places. East Germany? Sure. But, Bulgaria?

This is a basic reason why people should check out her work, including this book. How can you truly understand the Cold War (and its aftermath) without knowing about Eastern Europe? And, not just from the perspective of the West. This includes studying communism, which many people associate with a failed system – at best – an “evil” ideology at worst.

We need to know things from their point of view. Kristen Ghodsee provides this. And, she does so in a down-to-earth way, here by focusing on the lives of five leading women. Ghodsee does not glorify communism in the process. It’s not propaganda.

For those interested in the history behind the Russian Revolution and many of the people involved, this is a book for you. It is not a full accounting of its history or life in a communist country. And, if you just assume all communists are evil or misguided, this book is not for you.

This book is appropriate for the lay reader as well as those who are studying the cultures discussed. The book is intended for everyone. It has many photographs as well as a charming discussion of why the book is dedicated to her dog, Daisy.

The book, as is her norm, is relatively short. A person who is looking for a comprehensive account of the women (and times) covered in the book might wish to look elsewhere.

Comprehensive Summary

Introduction: Bourgeois Feminism and Its Discontents

The author teaches about “Sex and Socialism.” She teaches about the lives of women and men who are enemies of capitalism; even gender studies majors often know little about many of the leading socialist women. Western feminists dominate most gender studies courses.

One thing covered in her classes is disputes over feminism, including how best to promote socialism while still respecting women’s rights. This led to conflict between liberals and socialist thinkers, with liberals seen as favoring elites. A full understanding here helps us understand how to create, further, and defend social change.

Five female warriors (Valkyries) will serve as models.

1: The Sniperess: Lyudmila Pavlichenko (1916-1974)

Lyudmila Belova was born shortly before the Russian Revolution, a daughter of a factory worker and teacher. She got pregnant at fifteen, married (taking the last name she kept all her life), but soon divorced. Her mother looked after her son while Lyudmila continued her studies and worked at an armaments factory. Lyudmila also found she had an aptitude for shooting.

Lyudmila’s education, besides partially a result of Stalin’s fears of outside threats (thus the promotion of military training), is an early sign of the equality promoted by the Russian Revolution. Women, up to a point, were encouraged to get an education and training for jobs that would be deemed inappropriate for women in Western countries.

When Germany invaded the Soviet Union during World War II, Lyudmila (with some resistance at first, the recruiter suggesting nursing) used her skills to be a sniper. She eventually had 309 documented kills, the most of any woman sniper. She was repeatedly injured. Lyudmila also fell in love with a fellow soldier, though he was eventually killed in combat.

After her fourth war injury, Lyudmila was sent on a propaganda tour to the United States with two other (male) soldiers. The United States, including First Lady Roosevelt, was very impressed with her, though some were shocked at her “masculine” job. Soviet women still had to fight chauvinism at home, including women snipers being expected to do “female” jobs such as cleaning the barracks. Women resisted such sexism.

She later became a journalist and military historian but was most well known as a symbol of a female warrior. Her post-WWII life was often an unhappy one, plagued by depression and alcoholism. The chapter does not talk much about it; she is best known for her war experiences.

2: The Communist Valkyrie: Alexandra Kollontai (1872-1952)

Alexandra Mikhailovna Domontovich [Russians always have such long names] was born to wealthy politically liberal parents. Her background inspired her continual “aristocratic” style, which she retained for the rest of her life. She also had a stylish look, including makeup and hair.

Alexandra showed her independence at an early age, marrying a poor cousin (Vladimir Kollontai) at twenty-one, much to her mother’s horror. Her husband worked as an engineer and the poor working conditions she experienced encouraged her socialist ideas. She was but one of many in late 19th Century Russia inspired by socialist and communist thinking to reform society.

Alexandra Kollontai was particularly concerned about the status of women, including how traditional practices denied them rights. She argued the special needs of women required – for the good of communism itself – to focus particularly on the needs of women. Alexander eventually helped to form the Zhenotdel, a women’s section of the Communist Party.

She also was supportive of a free love philosophy, believing strict social structures (including marriage and traditional family) should not hold back personal and sexual connections. She had many affairs and multiple marriages, causing some problems for herself when others used her free reining ways against her. She promoted “comradely love.”

Alexandra eventually had an important role in the early years of Communist Russia. Her differences with the winning faction caused controversy, leading her to seek out diplomatic roles to find a safe place to serve Soviet Russia. She had a long successful diplomatic career between the 1920s and 1940s, surviving Stalinist purges. She died a few years after retiring.

Many of the pro-women moves she and others supported (such as easy divorce, abortion rights, and child support programs) were overturned in the more conservative Stalin years. A major problem was that there was a lack of resources and will to enforce the changes, resulting in the worst of both worlds (sexist practices without the minimal security of tradition).

3: The Radical Pedagogue: Nadezhda Krupskaya (1869-1939)

Nadezhda Krupskaya was born to free-thinking impoverished nobles, who nurtured independence and self-sufficiency in their daughter. She was a diligent student and found much satisfaction as a tutor for factory workers. This helped her regard education as a key part of socialism.

(“Socialism” is the name given to the existing situation in Soviet Russia, including the ultimate name of the country itself aka Union of Soviet Socialist Republics [USSR]. “Communism” was the ultimate ideal, not understood to have been reached for the time being.)

Nadezhda, unlike the previous Valkyrie, believed in an ascetic existence, like many socialists inspired by a character in the Russian utopian novel, What Is To Be Done? She had a deep passion for the cause of socialism, willing to serve the needs of others (including her future husband, Lenin), behind the scenes, to promote the cause. Her marriage itself might have been a marriage of convenience, including while she and her husband were in prison and exile.

Nadezhda was very important to her husband, providing emotional and physical support to his cause in many ways, including copying and sending literature and serving him when he was sick. Nadezhda was particularly interested in reforming the educational system though her ideas were too free-thinking for Stalin. They did inspire many others around the world later on.

Her husband died in the mid-1920s and she soon found herself on the outs from the powers that be. Alexandra Kollontai was able to have the safety of distance. Nadezhda continued to live in the Soviet Union, watching many of her old allies die in Stalinist purges. She tried to carefully stay loyal to the communist party while moderately dissenting from time to time.

Nadezhda’s legacy as a loyal supporter of the Russian Revolution and educational reformer would be honored after Stalin’s death. There is even a chocolate bar named after her.

4: The "Hot Bolshevik": Inessa Armand (1874-1920)

Nadezhda Krupskaya showed more emotional attachment in her autobiography to Inessa Armand (who Lenin also was very close to, perhaps romantically) than her husband.

We do not know as much about Armand as the other three women covered, both because she did not write an autobiography, and because many accounts whitewash some aspects of her life deemed inappropriate. Not only did a well-off husband help finance her career as a socialist, but it very well might be the case that she had a romantic relationship with Lenin himself while he was married to Nadezhda. Nadezhda was not as liberal on such matters as Alexandra.

Elisabeth-Ines Stèphane d’Herbenville was born in Paris. Her father was an opera singer, and her mother was an actress. She grew up in Russia after her parents died in a traditional middle-class upbringing. She married Alexander Armand from a well-off liberal-minded family.

Inessa Armand had four children. Her younger brother-in-law, with whom she had a child, inspired her to take up socialism. As with the other two women we examined, she was willing to risk imprisonment (and exile) to fight for her socialist beliefs. More so than the others (Alexandra only had one child; Lenin had no children with his wife), she also had to balance work and family, including ultimately five children, a husband, and one or more lovers.

Inessa met Lenin during an exile in Europe though at some point was aggravated by how much he expected from her. Inessa also eventually spoke her mind about her disagreements with Lenin. He did not appreciate this. Inessa continued her efforts to promote socialism during WWI and the beginning of the Russian Revolution.

The early years were a period of civil war and she wore herself out fighting on the side of the communists. She died of cholera in her forties. Lenin was crushed by her death.

5: The International Amazon: Elena Lagadinova (1930-2017)

Elena Lagadinova was born to a poor family committed to socialist ideals but in non-communist Bulgaria. As a teenager, she fought with the partisans against a government that allied with Nazi Germany. Ghodsee talks about this in her book The Left Side of History.

Bulgaria ended up a communist country in 1945. Bulgaria’s new communist constitution guaranteed full equality to women. This helped Elena to obtain a career in plant science. She won recognition for her scientific achievements.

Nonetheless, Communist Bulgaria was not a country with freedom of thought, and this often led to conflict between scientists and party members who guarded against their alleged disloyalty. Lagadinova, now married, wrote to the leader of the Soviet Union to argue that such “babysitting” was no longer necessary. The letter was intercepted by Bulgarian authorities.

Luckily, the leader of Bulgaria was open to criticism and concerned about constitutional requirements for women's equality. Lagadinova was appointed president of the Committee of Bulgarian Women’s Movement (1968). She worked in this role, obtaining international acclaim, until forced out when communist rule ended in Bulgaria in 1990.

Lagadinova was shunted aside as capitalism caused various problems in the country. She believed there could have been a middle way possible, a softer post-communism path. She recognized the old system had problems such as political repression, shortages, and failures to fully honor socialist protections like free lunches at schools. The author eventually interviewed her.

The heroine in the fictional film Goodbye, Lenin! was able to die dreaming that communism won in the end, her son staging the fantasy as both she and East Germany were dying. Lagadinova a few years ago died with a more harsh reality, including seeing the rising fascism in some parts of Eastern Europe. But, she continued to dream of a better world.

Conclusion: Nine Lessons We Can Learn from the Red Valkyries

The socialism that the women covered in this book fought for led to major improvements in the lives of the people in their countries. This includes such things as increased life expectancy, lower infant mortality, improved educational opportunities, gender equality, and more.

Ghodsee is sure to note the dark side as well, including the brutality of Stalinist rule. She recognizes the mixed legacy of each of the socialist valkyries discussed in the book. Their efforts led to much good, but they also died watching many of their ideals not winning out in Soviet Russia and post-communist Bulgaria. History is filled with mixed legacies.

Ghodsee ends with nine assets and traits that helped the socialist women. And, can help us all.

Comrades: the importance of a support network of family, friends, colleagues, and romantic partners. A whole community is essential to provide a foundation.

Humility: the value of accepting we are a small part of a wider movement, including not always having our efforts be recognized specifically.

Autodidacticism: a fancy term that means self-education, the value of acquiring knowledge and wisdom on one’s own and using it to inspire creative thinking.

Receptivity: an ability to have mental flexibility, to be able to change one’s mind and expand one’s horizons when warranted.

Aptitude: self-education and experimentation help us to discover our special skills and how to best use them for the greater good.

Coalition: an ability to work with others for a larger cause, even if there are strong disagreements among us in various respects.

Tenacity: being able to handle the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune” and fighting on. Showing up and fighting for another day even with doubts and immediate failures.

Engagement: finding ways to be involved such as speaking out, taking part in protests, creating various projects, and many more things in promotion of your ultimate end.

Repose: knowing that sometimes you need a break, gives you a chance to regain your energy for future battles.

Points to Ponder

Kristen Ghodsee wrote a book entitled Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism, a risque title that summarizes a more serious argument. Socialism for Ghodsee is not a bad word.

Ghodsee argues that “if we adopt some ideas from socialism, women will have better lives.” For instance, socialism promotes equality among the sexes and provides a safety net making life a lot more secure for women. This leads to better relationships and sex lives.

A book about women who championed communism might for some people be hard to find relatable. But, she wants us to look deeper, and see that what these women fought for was good in various ways. And, she does so without handwaving all the bad stuff like Stalin’s purges.

This is a lesson for studying historical figures, including in our country, as a whole.

FAQ

Kristen Rogheh Ghodsee is a Professor of Russian and East European Studies and a Member of the Graduate Group in Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania.

She has visited Eastern Europe regularly as part of her ethnographic [cultural] research and lived for over three years in Bulgaria and the Eastern parts of reunified Germany.

She has written ten other books:

Taking Stock of Shock with Mitchell A. Orenstein

Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism

Second World, Second Sex

Red Hangover: Legacies of Twentieth-Century Communism

From Notes to Narrative: Writing Ethnographies that Everyone Can Read

The Left Side of History

Lost in Transition: Ethnographies of Everyday Life after Communism

Professor Mommy: Finding Work/Family Balance in Academia With Rachel Connelly

Muslim Lives in Eastern Europe

The Red Riviera: Gender, Tourism and Postsocialism on the Black Sea

Is Red Valkyries a Reliable Source?

The author writes about what she knows. She is a professor of Russian and Eastern European Studies. She has done fieldwork in Bulgaria and Eastern Europe. And, she interviewed Elena Lagadinova, able to converse with her in Bulgarian.

Prof. Ghodsee also does not try to provide a comprehensive look at each of these women, which might require more expertise. Ghodsee studies Eastern European cultures, which includes the knowledge of the historical material covered by this book. Endnotes are also provided, if not the amount that would be in a more academic work.

Ghodsee also flags repeatedly when our information about women has gaps, not making assumptions based on limited source material. Overall, I found this a reliable source.

===

Note: If you like this book summary, many more can be found here.

The self-improvement ones are generally not mine. The others are. The website is run by someone else who is responsible for the final content. This entry is mine alone.