Juneteenth honors the day (June 19, 1865) when federal troops officially took control of Texas. Months after the surrender of General Lee at Appomattox and the assassination of President Lincoln, the Civil War was basically over by that point. But, under the dictates of the Emancipation Proclamation, official military control of Texas meant the permanent freedom of the slaves that lived there.

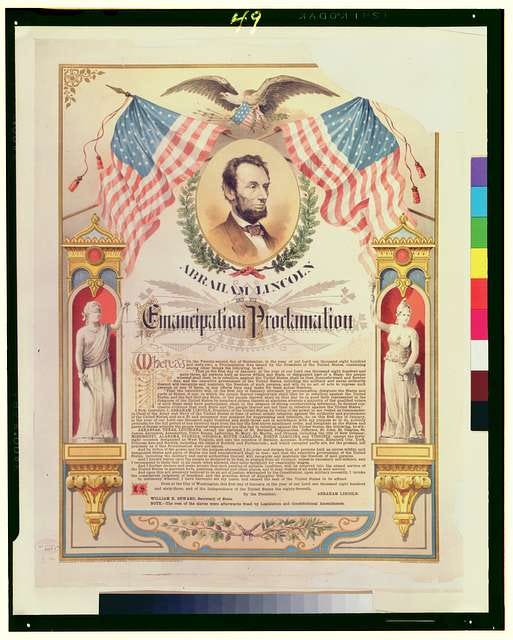

Was the Emancipation Proclamation, a Civil War measure that declared millions of enslaved people “forever free”? What were the benefits and costs of the measure? Some say it “didn’t do anything.” Others would applaud the event as a major milestone in our nation’s history. Let’s take a look.

Emancipation Proclamation: The Declaration

The Emancipation Proclamation was an official presidential declaration handed down at the beginning of 1863, right in the middle of the Civil War. The core message was front and center:

“all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

The U.S. Constitution at that time had various provisions that involved slavery. Those who wrote the document tiptoed around the issue, not using the word “slavery,” but rather referring to “other persons” or “labor” or “property.”

Sectional divisions over the issue of slavery plagued the nation from its inception. Compromises were attempted and failed.

By 1863, people were more blunt. We were dealing with “persons held as slaves” and this presidential declaration, with the force of law, declared millions of them “forever free.”

A War Measure

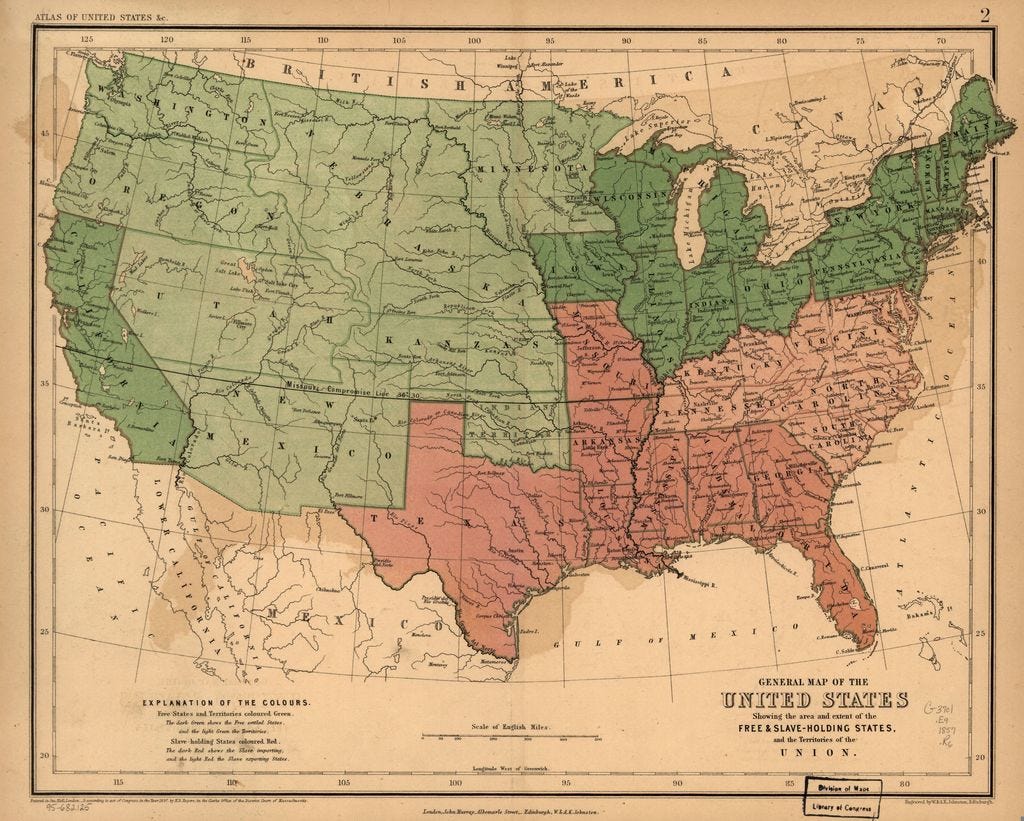

The Emancipation Proclamation was defended as a war measure, President Lincoln citing his power as Commander-in-Chief. All the slaves in the country were not being freed. Thus, it did not cover the nearly 500,000 slaves in the slave-holding border states (Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, or Delaware) which were Union states. Plus, there is a long paragraph spelling out Confederate areas then under Union control, such as large parts of Louisiana. This covered about 300,000 more slaves.

Challenges of the Emancipation

There were still around three million more slaves in Confederate-controlled areas. Not only were these people now declared free, but President Lincoln recommended them to be paid “reasonable wages.” They were also to “abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defense.” Self-defense would include the now legally freed slaves resisting attempts such as by their “owners” to keep them in slavery.

President Lincoln also cited a special personal duty to protect the people freed from slavery. He declared that

“the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.”

The military was now abolitionists.

Furthermore, these people before emancipation were deemed human property. And all states — even free states — had a duty to return to their “owners”. Such were the dictates of the federal Constitution. Now they were welcomed into the “armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.”

Lincoln finishes with a flourish:

“And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God.”

Benefits

A basic benefit of the Emancipation Proclamation is its moral weight. We should not lose sight of this while realizing it was also a pragmatic war measure, deemed a necessity to win the war.

The moral and symbolic power of the document should not be lost. Former slave Frederick Douglas spoke of the “shout for joy” made by many against slavery; one paper spoke of the great strive for “civilized progress.”

The nation was now officially duty-bound to support the freedom of about three-quarters of the slaves in the United States. Lincoln once declared that the country could not be both free and slave over the long term.

If so, even the slaves not covered by the Emancipation Proclamation were destined to be free. How to go about it on some level was a mere detail. The great evil of slavery was doomed.

The War Over Slavery

When the Civil War began, an official declaration was made by Congress that it was being fought to reunite the Union. Many did not want the war to be about slavery, and when President Lincoln proposed the Emancipation Proclamation, General McClellan — at times the Commanding General of the Union forces — felt such a move was “an accursed doctrine.” The abolition of slavery was now a war aim.

The Emancipation Proclamation was carefully timed after a major Union victory at Antietam to show it was not an act of desperation by the federal government in a weak position. “Confederates,” it said, “you are on notice!” Surrender or else.

A Blow to the Confederacy

They did not. The result targeted a basic Confederate resource, their forced labor supply. The Confederacy would not only lose their slaves but the now free persons would be welcomed into the Union military to help defeat them!

Slaves and freed blacks, including such leaders as Frederick Douglas, early on saw the war as a means to obtain freedom and attack slavery.

Thousands of slaves fled to Union lines, even before an official policy was in place protecting their freedom. But, the Emancipation Proclamation made freedom official. Once the ball started rolling, freedom’s reach would likely be ever expansive.

The Proclamation & Foreign Policy

The Emancipation Proclamation also had a foreign policy benefit. Great Britain, which the Confederacy tried to get on their side, had long supported the end of slavery. If the war was merely about reuniting a slave nation, why not support the Confederacy with its large cotton resources? France could follow.

Now, the Union was on the side of freedom. At the end of the war, the Confederacy was so desperate that it seriously thought about accepting abolition itself to survive. The Confederacy saw the moral attraction, the foreign policy implications, and even hoped slaves might help them. The war ended first.

Costs

Were there any “cons” to the Emancipation Proclamation? My extensive discussion of the benefits probably might be suggestive here.

But, things rarely are completely one way or the other, and the same probably applies here. I think the benefits win out, but you can judge yourself.

There is a continuing concern that the “ends justify the means” results in abuse of power and threats of civil liberties. Lincoln himself before the war made clear his belief that the federal government had no power over slavery in the states. That is why there was the need for a constitutional amendment to permanently ban slavery.

Benjamin Curtis, who wrote one of the dissents in Dred Scott v. Sandford (slaves in the territories), argued that the Emancipation Proclamation itself was unconstitutional.

What about, for instance, a loyal owner in a Confederate-controlled territory? What power did Lincoln have to permanently seize their “property”? If the legal argument was borderline, would it not encourage future governments during wartime to violate other rights, rights less immoral as well?

Would it be Temporary?

A somewhat related concern was the legal limitations of the Emancipation Proclamation. If it was a war measure, what would happen once the war was over?

It was the Thirteenth Amendment, not the Emancipation Proclamation that truly abolished slavery.

And, again, did it actually “not do anything” since it only applied to Confederate-controlled areas? The Emancipation Proclamation was a set of marching orders. Freedom followed the Union Army.

Still, the mere promise of freedom was not enough to protect the rights and well-being of former slaves. The Union army brought freedom and some degree of security to the now free people. But, the army could only do so much, and what happens when it leaves? The Emancipation Proclamation alone did only so much.

The Emancipation Proclamation also is not very eloquent, especially as compared to some things President Lincoln said and wrote. It has been compared to a “bill of lading” or a receipt for a bunch of goods. Again, this is not fair even as to its text. But, its eloquence is in its actions.

Did it Increase Sectionalism?

One final concern might be the divisive nature of the Emancipation Proclamation. Democrats used it as a campaign tool, arguing it was an abuse of power and a horrible abolitionist document. Many still were wary about the total end of slavery.

It also helped the Confederacy by showing how “horrible” the Union winning the war would be. The Declaration of Independence, after all, included an allegation that the English were “exciting domestic insurrections.” That refers to slave rebellions.

The benefits outweighed any divisions arising from a somewhat controversial measure. Also, even here, slaves were already fleeing to Union lines. The military was no longer returning slaves to their owners. Lincoln and the Republicans were already damned as anti-slavery, power-hungry devils. Democrats and Confederates had political ammunition already.

Juneteenth and Beyond

June 19th or Juneteenth completed the process set forth by the Emancipation Proclamation. Courts would later hold that Union control resulted in the freedom of the slaves in the area covered.

The Thirteenth Amendment was ratified in December, finishing the job of abolishing slavery.

But, as the author and journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates once noted,

“emancipation is itself a part of an even larger process — integrating African Americans as citizens of equal standing. That effort continues even today.”

Juneteenth is now a federal holiday. And, the effort continues.

==

Note: This is a slightly edited form of an essay on another website. The website owner supplied the photos. Our editing software was less strenuous back then.

President Andrew Johnson officially declared the Civil War over in mid-1866. The “end” is usually cited as Lee’s defeat at Appomattox. Nonetheless, there was still some “clean-up” to do. There was even a final battle in May. A Confederate victory.